The other day, it being a holiday, I thought I’d dedicate the morning to a spot of birdwatching in Tommy Thompson Park, that thin finger of industrial wasteland reclaimed by nature that makes Toronto a haven for migrating birds (while the rest of the city does its best to destroy them – with its tall buildings, roaming cats, and pollution of various kinds).

I don’t claim to be a birder. They are a breed apart, as far as I’m concerned. I don’t have their dedication to the hobby. My binoculars aren’t particularly high-powered. I’m just as interested in common birds as rare ones – I get a lot of joy from watching sparrows hopping around on the sidewalk and am more attracted to bright colours than being able to tick a name on a list. And a rare bird to me is only one I haven’t seen before.

But I do love birds. The wonderful delicacy of their makeup, the beautiful intricacy of their design, and the endless variety of species fascinate me. Not in a scientific way so much as in a visceral wonder at the beauty of the natural world so far beyond anything we are capable of creating. Flowers do that for me, too.

I went early in the morning but not crazy early – I have my limits (and so does the TTC), and as I’ve said, I’m not actually a birder. But I went early for two reasons: because wildlife is more active around dawn and dusk and to avoid the inevitable crowds. The five-kilometre strip of paved road running end to end seems to be popular with cyclists. At times, later in the morning, there were so many men in Lycra zipping past you’d think you were on the Tour de France.

But at 8am, it was still relatively quiet in terms of human activity but a riot of birdlife. There was tons to see without even leaving the paved strip, while towards noon it was much sparser with a few species like red-winged blackbirds and robins dominating the scene.

This being only my second visit to the park, I made it my goal to reach the end of the spit. I don’t particularly recommend it. You can get a good view of the Toronto skyline, but in my opinion, it’s not really worth it, and I certainly won’t be doing it again.

There’s nothing wrong with that part of the park, but it takes over an hour to walk out there (just walking, no stopping to look at anything) and the same to get back. That’s two hours I could have spent just being with nature.

No judgment on anyone who prefers to stick to the paved road and enjoy the trees from a distance, but given the option between hard asphalt under my feet with cyclists shouting to each other about work and the soft feel of earth and grass combined with the sound of wind and birds in the trees, for me there’s really no contest.

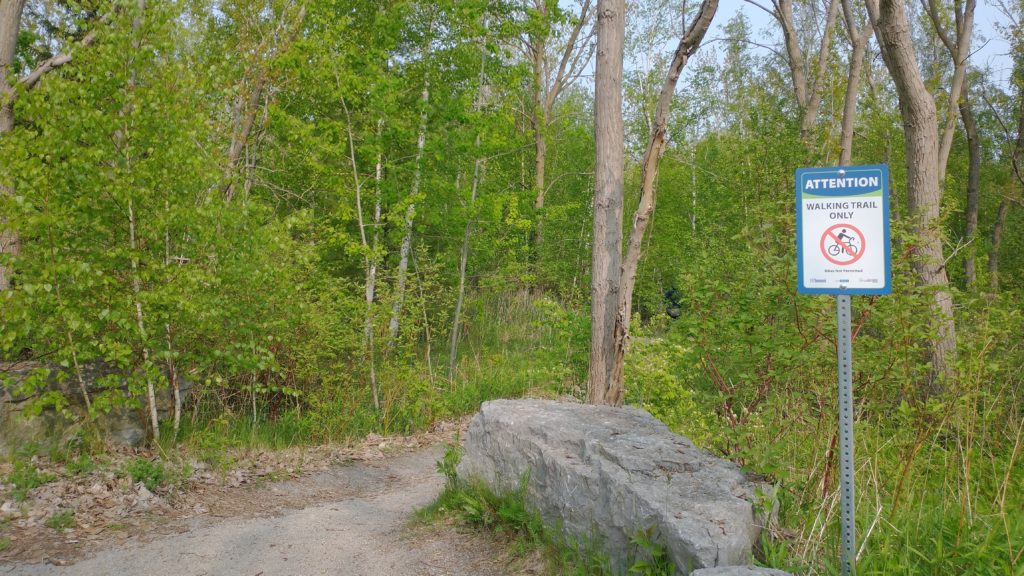

Even so, access for humans is limited, and it is very clear that humans are not the priority here. I found that rather novel and refreshing. I didn’t get far down one of the longer distance foot trails when I was confronted with a fence and a sign warning me that if I proceeded any further I could be prosecuted. However, the noise of what seemed to be the world’s largest pigsty convinced me even more that I probably wanted to go no further.

I supposed the denizens of the nesting site to be cormorants based on the numbers flying in and out of the forbidden zone. And I have since been informed that their excrement is extraordinarily smelly, so I guess the powers that be were protecting me from the birds as much as them from me. I’ve also learned that it’s particularly acidic, which is why the researchers at Tommy Thompson Park encourage ground nesting among the cormorants. When you see stark white tree skeletons poking up around the park, you are looking at evidence of where cormorants have nested in trees.

But cormorants weren’t the only birds I spotted. In the four hours I spent at the park, I saw at least twenty species – none of which, I should say, are rare and nearly all of which I was able to identify on sight, apart from the yellow warbler, which was new to me, and – possibly – a red-eyed vireo (I am spectacularly bad at matching birds in a tree with photographs in a field guide).

And that in itself makes you realize just how rich our local birdlife is right here in the city, even though we often only see pigeons and sparrows, and how important our microenvironments are.

Between the goldfinches, orioles, and yellow warblers, there were enough bright colours to keep me happy, and I was thrilled when a gorgeously plumed male cardinal darted across the wooded path mere inches from my face, though they are one of the least rare of all.

One highlight of the visit was being able to assist a fellow bird enthusiast. Seeing an orange flash high up in a tree by the roadside, I stopped to train my binoculars on it. A young man and an older woman were approaching from the opposite direction and paused behind me (mother and son, I presume, though I didn’t ask).

“There’s something up there in the tree,” said the man.

“It’s an oriole,” I told him.

It turns out the woman had come to the park that morning on a specific mission to see orioles but had so far had a fruitless search. I was glad to have been able to help, but considering I later saw about a dozen orioles throughout the morning makes me think she had been particularly unlucky.

Birdwatching, as with any potential interaction with wildlife, often comes down to luck. And I think it’s a good thing to go out into nature and experience these lucky and unlucky moments – even if only in our urban parks. It’s one way to help reality break through into the otherwise highly structured, predictable existences we have created for ourselves in our modern, Western, urban society. It’s healthy to have an outlet from time to time, somewhere we can go without expectations and let go of our need for certainty and control and open ourselves to whatever blessings may come.

It’s important, too, for those of us in the city to make time and find opportunities to immerse ourselves in nature. It’s an inexpensive antidote to all the ills and stressors of urban life. In Toronto we are fortunate to have some decent parks at our disposal. Although they are, admittedly, a tame, controlled vision of nature, they are nevertheless vital oases and a significant public resource. So let’s get out there and use them.

Hi, Kristina. This is a nice introduction to your writing for me! Though I tend to look down at plants more than up at birds, I am trying to become more acquainted with the latter. There was an unfamiliar warblerish sound this morning right near St. Basil’s that my Merlin app identified as a bay-breasted warbler. This is a hard-core migrant that passes through Toronto as quickly as possible to nest in the boreal forest. I was rewarded with the sight of it – long and skinny like an airplane fuselage, skittering through oak leaves. Its rich maroon-coloured flanks were not that evident, as the bird was largely silhouetted. But there it was.

Thanks, Gavin! That’s neat that you were able to spot the bay-breasted warbler right in the middle of downtown. You’ll have to show me the app next time I see you.

Love!